In 2025, I was commissioned to write an essay to the first edition of Meander — a new magazine "for bioregional culture, slow living, and regenerative futures".

In this piece, I explore the deep history of our relationship with gardens and gardening as a species, and consider the eco-philosophical significance of gardens for our own time.

My earliest memory is of a garden; specifically, part of the garden of my second childhood home. I would have been perhaps three or four at the time, and there was a secret space that existed between the back fence and a large hedge that was planted up against it. To any adult it was entirely without interest, being far too small and low to the ground to either invite or admit entry. I, however, being small, was able to comfortably crawl into it, and to enjoy what was secluded there beyond the adults’ reach; a magical, miniature bower.

I’ve visited a great many gardens since, far more lavish and beautiful than that space behind the hedge. But none has ever given me anything like the intensity of enchantment and imaginative possibility that I remember feeling there as a child.

I tell this story because, in some way, it’s emblematic of a much deeper desire running throughout Western culture: the desire to go back to the Garden. It’s no coincidence that the Garden features so prominently in utopian literature and projects — from William Morris's News from Nowhere, to Ebenezer Howard's garden cities, to the commoning experiments of Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggers. They share in common the unavoidable influence of one of the oldest, most powerful utopias — the originary myth of the Abrahamic religions – the Garden of Eden.

Our expulsion from Eden has long functioned as a metaphor for our disconnection from nature. Taken together with Enlightenment and Romantic narratives, this myth helped fix a story in the Western imagination: that humans once lived in harmony with nature, only to fall from grace as a result of our appetite for knowledge. We were condemned to live “by the sweat of our brows” (that is, through the hard work of growing food, rather than the easy work of simply foraging it).

It's a powerful and persistent story, but also a misleading one. In The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow share evidence that a linear progression from foraging to farming derives heavily from the influence of these narratives. The evidence also shows such narratives to be overly reductive and historically inaccurate. In fact, rather than a binary rupture, the so-called "agricultural revolution" was a protracted, pluralistic, and ultimately contingent series of events. Indeed, human societies have long moved fluidly between different modes of living, often blending foraging with cultivation, art and ritual with practical necessity, and movement with settlement.

Etymologically, the words "culture" and "cultivation", as well as "cycle", share a common root. They all derive from the Proto-Indo-European source *kwel, meaning "to revolve, move around", and/or "to sojourn, dwell". Paradoxically, then, we have both a going and a staying; a settling which depends on moving, and yet this makes perfect sense when viewed in the context of our development as a species.

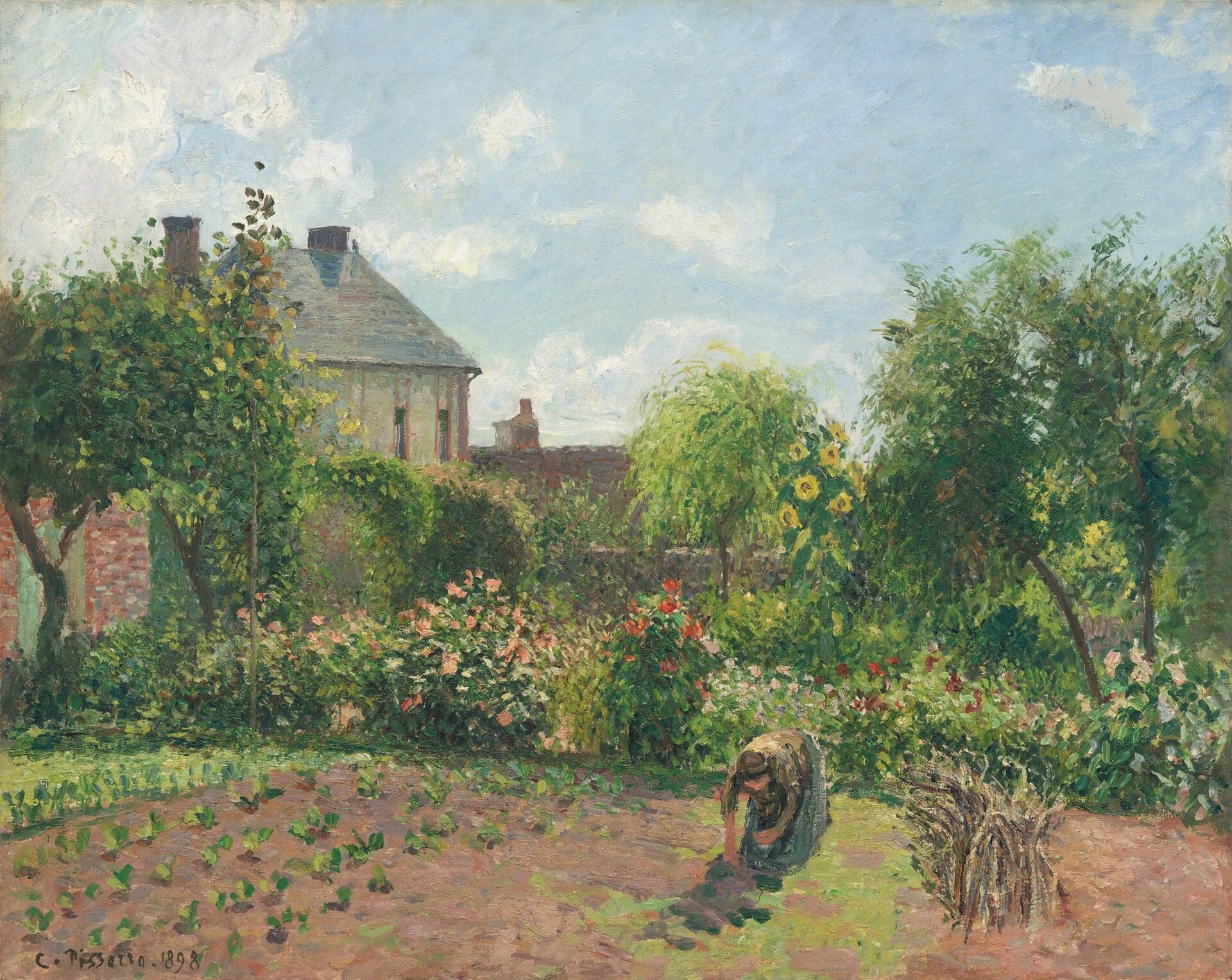

As a product of human artifice, gardening is essentially the deliberate design of ecological niches to ease inhabitation. Due to their direct experience of the landscape, nomadic and semi-nomadic hunter- gatherers were far more skillful gardeners than contemporary humans. Travelling seasonally from place to place, they acted as stewards of the places they were moving through, carefully managing their region's ecosystem.

To this extent, the history and nature of the Garden "helps us to rethink a highly debated transition in the history of the human species: from hunting and gathering to sedentary life.

Indeed, human societies have long moved fluidly between different modes of living, often blending foraging with cultivation, art and ritual with practical necessity, and movement with settlement.

In this picture, the supposed dichotomy between human culture and nature quickly begins to disappear. It also involves a far richer and more expansive concept of 'gardening' than we tend to hold in the modern imagination. For the most part, the contemporary garden represents a scene of ornamental control and privatised retreat, safe from needing to think too much about the ecological or political implications of one's way of life.

Radical roots

In reality, gardening always involves an entanglement with questions of power. This is as true of the humble gardener constructing a small fence to protect her vegetable patch, as of monarchs and other elites who, throughout history, have created gardens to reinforce and ‘naturalize’ their status. Where one finds empire or colonialism, one also tends to find gardens. But while the Garden can be used to exercise domination and exclusion, it can also carry the seeds of grassroots collectivity and resistance.

Movements like guerrilla gardening, permaculture, and food sovereignty, which draw on indigenous land practices, reclaim cultivation as a site of communal agency, pushing roots through the cracks in capitalism's infrastructure. The word 'radical' itself, from radix, Latin for 'root', reminds us that to go to the root of things is both a political and ecological gesture.

Faced with worsening ecological and social crises, it’s tempting to romanticise the Garden, just as we have romanticised ‘Nature’, as a kind of panacea; to imagine that we could recover an Edenic state of perfect harmony (and indeed to imagine that such a thing actually existed in the first place). But this sort of nostalgia is the very same impulse that has led to ‘Take Back Control’ politics, stemming from fear of the future, denial about the present moment, and misguided attempts to recover an idealised version of the past. Perhaps, instead of avoiding the complex messiness of history, we might think about how to compost it — how to create the conditions that will help break it down, allowing us to grow something more beautiful from its remains.

How might we seed a horticultural renaissance? What might the Garden look like if we treated it not as an object of mastery or decoration, but as a theatre for rehearsing more connected, contemplative lives; for practicing more-than-human relationality; for opening ourselves to spiritual renewal?

Authors like Richard Mabey, Sue Stuart-Smith, Michael Pollan, and Olivia Laing have explored how gardens offer us a transitional space in which we can not only ask, but live into such questions. A space where the distinctions between labour and leisure, imagination and materiality, self and world, begin to blur. Indeed, in tending a garden, we are also tending our own inner landscapes. “I am working hard in this field”, wrote St Augustine, in his Confessions, “and the field of my labours is my self.” It’s an appropriate metaphor; the work of cultivation also teaches us something of humility, attentiveness, reciprocity – and of what it means, ultimately, to be a participant in the great mystery that is the cycle of life and death. When turning the compost, I’m always reminded that I, too, will one day be gardened back into the earth.

St Augustine’s conversion, in the garden

Connecting through practice

The philosophical and spiritual potency of the Garden comes not only from reflection, but from practice — from a grounded, embodied engagement with the specificities of place, and with how a place supports life. This means learning the soil's profile, the micro-climates of a plot, the needs and tendencies of particular species. It means reattuning ourselves to the weather, to natural patterns and cycles, to ecological limits. In our digital age we seem to have forgotten that our survival in fact depends on the soil, gardening can quite literally bring us back to our senses.

Bioregioning starts in the garden

In relation to bioregionalism, gardens — particularly public and communal gardens — represent a unique opportunity to link personal, local, and systemic forms of participation and exchange. Gardens produce herbs, fruits, and vegetables — and just as importantly, they also produce conversations and relationships, forming networks of reciprocity and mutual support that resemble the interlacing threads of a mycelial web. Whether it’s sharing seeds and cuttings, lending or borrowing tools, or participating in the production of local food, gardening tends to teach us something about what ecologically appropriate, regional economies can look like.

If bioregioning is a movement toward place and belonging, then gardening is surely one of its most immediate and accessible expressions. It does not require specialist knowledge or large-scale infrastructure — but only a few simple tools, and a willingness to get one’s hands dirty. As Wendell Berry writes:

I can think of no better form of personal involvement in the cure of the environment than that of gardening [...] If we apply our minds directly and competently to the needs of the earth, then we will have begun to make fundamental and necessary changes in our minds.

We might say, then, that bioregioning goes beyond simply drawing new maps, gesturing instead toward a deeper transformation; toward new ways of relating, dwelling, being. New — but also, perhaps, old and ancient at the same time; a way of moving forward which is also a returning to roots. This, I suggest, can be the movement of culture and cultivation. This can be the movement of the Garden.